I always appreciate the news according to The World Tonight, especially on Robin Lustig's watch. It is vital that we take in a broad sweep of the issues which are important to our everyday lives.

And I think The World Tonight is often the best at this - by miles, in comparison with other BBC news output for the UK. Lustig has recently posted on his blog his theories about why the current swine flu is a 'flu scare'. Of course, most of his concerns about scaring people lie with how it is presented by health experts and the media.

But he makes this point: 'We live in a complex, confusing, technologically-challenging world.... We lie awake at night and worry: do I know enough, understand enough, to make the right decisions for myself and my family?...But the answers are usually as confused as the questions.'

Lustig may have noted that people are generally less willing these days to accept what they are told by officialdom, but something is else is also going on.

Because the modern world - particularly medical science - has advanced to such a detailed state, we as humans have an overwhelming urge for someone to tell us 'it's OK - we know what's happening'. And we invariably turn to an expert in the particular area of concern, whether it be a cancer doctor or an infectious disease specialist, for that essential reassurance.

So what would be the result if a virology expert turned round and admitted about the current H1N1 flu strain:'Actually this is so globally complex and new that we don't have any idea how this will develop or how to effectively protect ourselves.'

Panic!!

And, though we do have a few pointers for how the pandemic may move and change, it seems true to say the experts have little idea where this may all be heading, or why it is happening now.

But it is 'only flu' as Lustig and others protest. 'Just wash your hands!'

Again that heartcry for simplicity and reassurance erupts.

The official advice that people with 'underlying health conditions' need to be careful about coming in to contact with the virus is a simplistic message masking a whole new world of unknown factors.

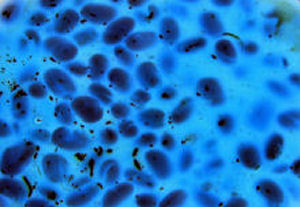

Evidence is emerging from international biomedical expertise of even greater complexities in our bodies than we have ever imagined, involving a community of many more genomes than our human genome!

The Human Microbiome Project

states that 'within the body of a healthy adult, microbial cells are estimated to outnumber human cells by a factor of ten to one. These communities, however, remain largely unstudied, leaving almost

entirely unknown their influence upon human development, physiology,

immunity, and nutrition' (my emphasis).

Please - take a deep breath and don't panic.

Yes, we still have some way to go to understanding what it is happening at a bacterial and virological level.

But, if we as patients - as well as that lumbering medical establishment, so slow to adjust - take a step back from the detail of our bodies then we may start to observe a few patterns in the complex mesh of human metabolic processes.

Too often we rush to doctors who prescribe the necessary treatment for the current complaint - stop that pain, cut that part of the body out, try this prophylactic treatment.

But how come several different symptoms, noted in different parts of the body by different specialists,are happening in the same body?

Should I be considered so dilettanteish for mentioning that, for example: an infected wound requiring amputation is attached to a diabetic body with increasing vision defects; or gastroenteritis suddenly occurs in a person with a heart condition given antibiotics for pneumonia; or a teenager with early onset arthritis in their joints also suffers with chronic fatigue and acne?

Surely if we push and pull our bodies around in a blinkered manner, as specialist doctors tend to, the microbial communities within will break out in to a fist fight too - and may enlist some viral thugs to join forces.